Mechanisms of Remote Influence in Afro-Diasporic Traditions: An Anthropological, Metaphysical, and Psychophysiological Analysis

Vodou remote influence operates through the "porous self" and sympathetic magic, utilizing biological taglocks to target the soul's Ti Bon Anj. Rituals like sending a pwen or expeditions bridge distance. Scientifically, efficacy relies on the nocebo effect, social ostracism, and "Voodoo death," where intense fear triggers fatal physiological collapse.

The Supreme Sovereign of the Invisible: An Exhaustive Theological and Anthropological Analysis of 'Bondye' in Haitian Vodou

Bondye is Vodou’s supreme, remote creator and ultimate source of vital force (fòs). Unlike active lwa spirits, this "Deus Otiosus" remains distant yet essential. Rooted in African monotheism but named from the French "Bon Dieu," Bondye represents absolute destiny without an evil counterpart.

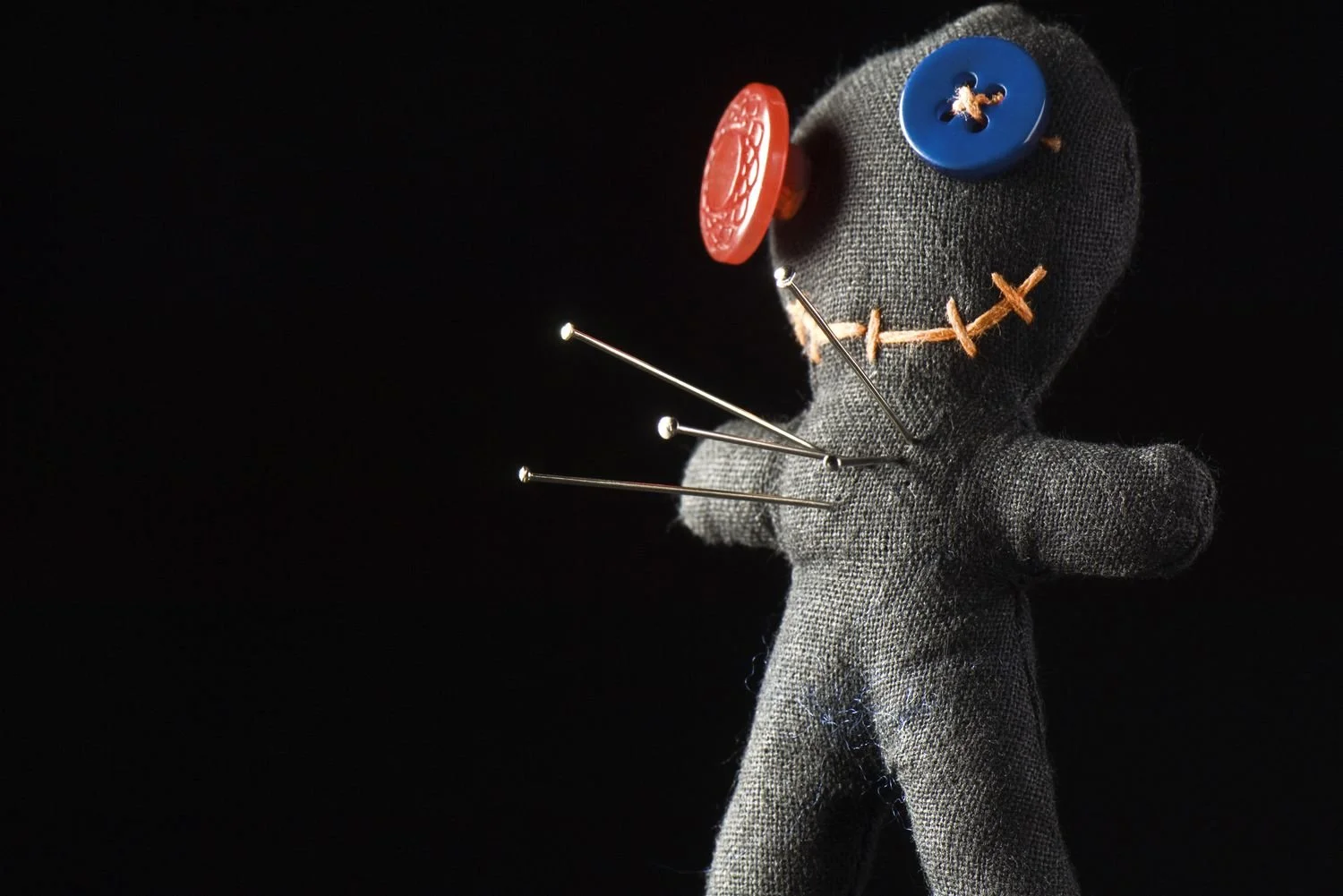

The Voodoo Curse: An Analysis of Religious Practice, Colonial Stereotype, and the Psychology of Belief

Haitian Vodou is a sophisticated religion distorted by colonial racism into the "voodoo curse" caricature. While authentic pwen and wanga utilize spiritual energy, the "curse's" power is largely psychological: the nocebo effect can trigger "voodoo death," where intense fear and belief induce fatal physiological collapse.

Kinetic Liturgy and the Architecture of Ecstasy: A Comprehensive Analysis of Dance, Trance, and Ritual 'Wildness' in Haitian Vodou

Vodou dance is not chaotic "wildness" but a disciplined liturgy where polyrhythmic drumming induces trance, allowing spirits (Lwa) to possess devotees. This state, governed by ritual laws, facilitates psychological catharsis and historical remembrance. What appears wild is actually the precise choreography of the divine entering the human vessel.

The Crossroads of Faith: An Analysis of Voodoo, Catholic Syncretism, and the Symbiosis of Papa Legba and Saint Peter

Voodoo, a resilient West African diasporic faith, syncretized with Catholicism to survive slavery by masking spirits (Lwa) as saints. Central to this is Papa Legba, the spirit world's gatekeeper; he is paired with Saint Peter because Peter holds the "keys to the Kingdom," creating a powerful shared symbol of spiritual access.